Search this section

APPROACHES TO LEARNING

An approach towards Conflict Prevention and Peace Building (CPPB) training, or the construction of CPPB training programmes, concerns the broad understanding of what guides the training. Often, such understanding remains implicit and grows from evolving practices within training institutes and practitioners organisations such as international organisations, state governments, NGOs and other civil society actors. Training approaches guide the type of content delivered, how the content is delivered (the methods), trainer-trainee interactions, and types of evaluations, but also the timing and sequencing of training moments, and the competencies addressed, whether these are Attitudes, Knowledge, and/or Skills (ASK).

Even though training approaches often remain implicit, several approaches can be analytically discerned from each other. In practice, however, aspects of several approaches can guide a training all at once depending on the styles and practices of training organizations and individual trainers. This is often only natural, as each approach has its benefits for training.

PeaceTraining.eu has distinguished several possible training approaches and provides further explanations on them in the following pages. The table below summarizes the approaches and their core principles. Note that the approaches can emphasize different aspects of training. The approaches listed were chosen because of their common usage in CPPB training, or there potential to positively impact future training development.

| Approach | Core principles |

|---|---|

| Prescriptive approach | The trainer acts as the expert and (sole) source of knowledge. Can be considered hierarchical. |

| Elicitive approach | Trainer and participants are equals and both are sources of knowledge. Trainer acts more as a facilitator to participants’ learning experience. |

| Adult learning | Close association with the elicitive approach. Coined by Knowles, adult learning assumes adults learn differently than children and that they must be engaged in the learning process. |

| Work-based learning | Work-based learning (WBL) refers to learning which takes place in the working environment – in an organisation, agency or mission – through participation in work processes or accompanying learning processes. |

| Experiential learning | Experiential Learning (EL) approaches to training are those in which participants learn by doing. Experiential learning immerses participants in an experience. Learning occurs through the combination of doing and experiencing, and reflecting on the experience. |

| Sequenced training approach | In a sequenced approach to training, participants progress in sequence through different trainings, often from introductory to more advanced levels. Typically, advanced trainings build on competencies developed in previous phases. |

| Coaching | Coaching can be described as an approach to improve performance competencies. It represents ‘one-on-one’ processes providing customised, tailored support to improve performance and capabilities of the practitioner. |

| Ecological approach | A novel approach which is characterized by awareness and engagement from the community, a holistic approach to the content and process of training, and practical, applicable learning. |

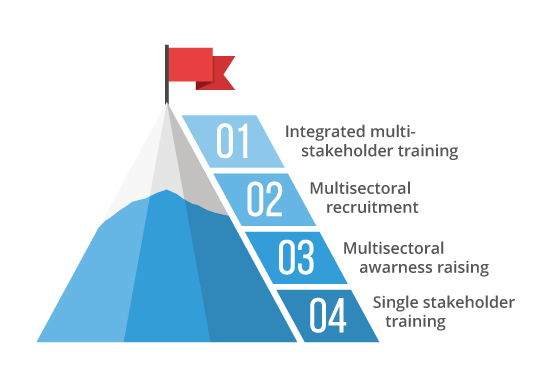

| Single-stakeholder training | Training content and target audience are focused on a particular CPPB sector (or organization), e.g. military, police, judiciary, humanitarian. The focus lies on building expertise in the sector/function. |

| Multi-stakeholder training | Training content and target audience are focused on different sectors active in CPPB. The main objective is to engage sectoral expertise with each other and learn how to work together in CPPB activities. |

Introduction

In a Prescriptive Approach to training, the trainer’s role is to teach the participants content or skills. The trainer may stand at the front of the room and present content to the participants. This may involve informing participants through a presentation or lecture. The knowledge is absorbed by the participants, without significant regard to variations in their background or expertise. Additionally, in this approach, trainers may demonstrate how to implement a model (for example, how to mediate a dispute) and then provide an opportunity for participants to develop their skills through a role play in pre-determined scenarios. Here, trainers act as coaches that show participants how to improve their technique (Loode). What makes this approach prescriptive is that the trainer may assume that the model demonstrated is universally applicable to different contexts and that the trainer does not generally incorporate participant feedback into how it may be adapted for diverse contexts.

Hierarchy of Trainer over Participants

The prescriptive approach to training assumes a hierarchy between trainer and participants. The trainer is seen as the source of knowledge and the participants are considered passive recipients of knowledge. In this model, the trainer often stands in front of the group imparting information on the participants while participants take notes, ask questions or quietly listen. Participants do not contribute their expertise to the training or have an opportunity to reflect upon or discuss its applicability to their own lives or work.

Universality

It is assumed that the knowledge is universally applicable to any situation (Young). For instance, participants may be trained on a set formula for negotiation, and they are not expected to deviate from that formula. Context and diversity may not be prioritised and may only be an add-on to the main material. If one examines gender or cultural sensitivity, it is seen as an add-on to the pre-existing material, rather than part of the training as a whole.

The prescriptive approach can allow participants to receive information from experts. Lectures from Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) can allow an audience to learn from the expertise of someone else. For instance, participants may benefit from a lecture by personnel who have recently returned from deployment on what to expect. In addition, lectures can communicate a large amount of content in a short period of time. For example, participants may benefit from a history lesson or a training that informs them about legal matters.

Another advantage to the prescriptive approach is its consistency and measurability. Funders may favour a programme that provides measurable and consistent results. Prospective trainees may know exactly what information they will receive because the material is fixed. It also means that trainers do not have to rely on audience contributions for the success of the training. Finally, many training participants want to feel that they are learning from experts, which this model offers.

The most significant drawback to the prescriptive approach is that it does not adapt to the needs of the participants and views diversity as irrelevant to a training. It assumes universality of principles, concepts and experience. This may be effective when working with homogenous populations but can be less effective when working with diverse and/or marginalised people. Moreover, if the trainer lacks sensitivity to diversity, he/she can fail to instil respect for diversity as a value in training. Finally, participants may be less engaged because the training does not incorporate participants’ experiences, affirm their expertise or follow principles of adult learning.

Peacebuilding trainers have found that a one-size-fits-all approach can be quite limiting. Loode(69) discusses the way that different understandings of concepts such as mediation or neutrality among different cultural groups can impact what type of intervention is appropriate. However, if trainers are able to adapt jargon and concepts to local contexts, work together with local partners on how a model may be applied in a specific context, and acknowledge to participants adaptations that may need to be applied to different populations, then this approach can still be successful (Loode 68, Abramson 2009).

In addition, trainers can:

- Ensure this approach is appropriate for the type of information you are conveying in the training. It may be better suited for transferring content rather than for participatory and transformative experiences.

- Acknowledge the experience in the room even if the training does not utilise it. Participants will respond better when they feel affirmed.

- Ensure SME’s speak from their own experience rather than presuming to be the ultimate authority.

- Provide alternate activities. Even if all of the activities are highly structured, giving participants a choice increases their agency and provides room for diversity.

- Know when this approach can be limiting and integrate it with others – experiential, elicitive, arts-based, etc.

- Abramson, H. “Outward Bound to Other Cultures: Seven Guidelines.” In C. Honeyman, J. Coben, and G. De Palo (eds.), Rethinking Negotiation Teaching: Innovations for Context and Culture (pp. 293–313). St. Paul, Minn.: DRI Press, 2009.

- Loode, Serge. Navigating the Unchartered Waters of Cross-Cultural Education. Conflict Resolution Quarterly. DOI: 10.1002/crq

- Young, Douglas W. Prescriptive and Elicitive Approaches to Conflict Resolution: Examples from Papua New Guinea. Negotiation Journal. 14 (3), 211-220, 1998.

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

In an elicitive approach to training, the trainer acts as a facilitator of a collaborative learning process. Similar to experiential learning, an elicitive approach often involves activities and then group reflection around issues that arise from those activities. Content is not ‘delivered’ as such; rather, learning emerges within the training through co-creation, collaboration and drawing both upon the trainer's and participants' knowledge, experience and expertise. This approach focuses less on retaining facts and more on being a transformative experience where participants attitudes may be shaped and their skills developed. Inclusivity and respect are embedded in the training. Cultural and gender sensitivity are incorporated into the curriculum. The knowledge and experience that participants bring to the training is valued, and participants are actively involved in the training process. Learning occurs through problem-solving, group work, and reflection. The training is made applicable to the participants’ lives and work.

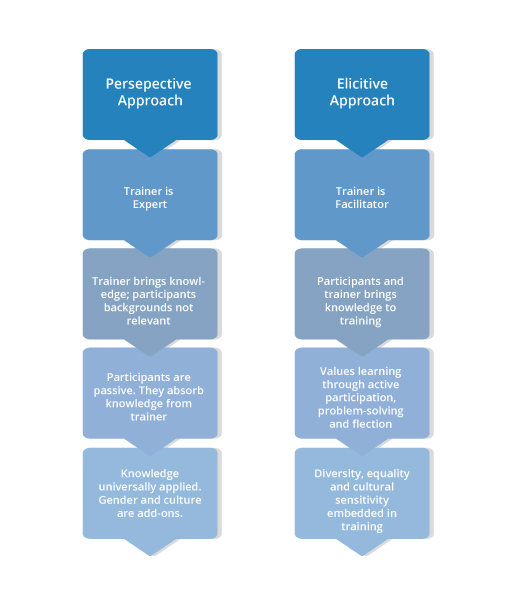

Lederach (1995) describes two possible approaches to training and education, the prescriptive and elicitive approaches. Within the prescriptive approach, the trainer takes on the role of expert and only source of knowledge, while the participants’ goal is to absorb knowledge from the trainer. Prescriptive trainings often make use of the lecturing method, for instance. The backgrounds and prior knowledge of participants are not generally brought into the training. The elicitive approach, which is highly compatible with Knowles’ adult education, incorporates the experience of participants into the trainer and allows participants to learn from each other as much as the trainer. Here, the trainer facilitates an experience whereby the participants actively engage in the material and with each other. They may practice skills and experience group activities as well as analyse and reflect on the modules. Through such an approach, the trainer can help participants apply the content to the real world.

Figure: Prescriptive versus Elicitive Approach to Peace Education (adapted from Lederach, 1995, p. 65)

Core characteristics:

- More Equitable Relationship Between Trainer and Participants: In the Elicitive Approach, the trainer takes the role of facilitator rather than expert. S/he acknowledges and values the pre-existing knowledge of participants and incorporates it into the training. Their knowledge is valued and included. Additionally, the trainer is responsive to participant needs and adjusts the training to their specific learning goals.

- Recognising and Valuing Context: The trainer tends to work with local partners, develops needs assessments, and acquires an understanding of how language and practices may need to be adapted for a particular context. Contextual understandings of conflict are acknowledged and discussed (Young). During the training, issues of diversity and power hierarchies are explored and reflected upon.

- It adapts to the needs of participants. Participants give feedback and training is made relevant to their work and experiences.

- It recognises diversity and integrates sensitivity into trainings. It takes into account culture and prioritises local partnerships.

- It follows principles of adult learning, including incorporating the expertise of participants and engaging participants as agents in the learning process.

- It adapts to the needs of the context.

- It catalyses participant reflection and facilitates transformative learning.

- It requires a highly skilled trainer. If the trainer does not conduct needs assessments with participants, establish ground rules, and properly facilitate the group experience, the risk exists that the training is derailed, for example by some uncooperative participants.

- A potential drawback is that the training process usually takes longer and requires significant upfront investment in introductions, ground rules, and group processes.

- It risks perpetuating cultural relativism, which can inadvertently result in the trainer reinforcing the power hierarchies rather than challenging them (Galtung 1990).

- Often, those who come to a training want to feel that they are learning something new, and sometimes this model can make participants feel that they are not getting enough expertise. This can be accommodated by merging trainer knowledge with local knowledge and varying the types of activities.

- The dialogical process is rooted in Western ideology and may promote Western assumptions. This can be overcome through addressing this in the training and acknowledging bias.

- Requires a highly skilled trainer skilled in group facilitation. The trainer must be prepared to adapt to issues as they may arise.

- Pre-training work, including participant selection and needs assessments, is crucial to ensure diversity of participants, that trainers cater for needs and goals of participants, and that participants know what to expect.

- Introductions, ice breakers, and ground rules are crucial for establishing trust and community among participants.

- Recognise power hierarchies and biases as they emerge in the training. Grapple with them together with participants.

- Check in regularly with the group to adapt to (new) needs.

- Work with local co-trainers. This can increase legitimacy of the programme. However, it requires an even greater investment of time to build relationships and train trainers.

- Abramson, H. “Outward Bound to Other Cultures: Seven Guidelines.” In C. Honeyman, J. Coben, and G. De Palo (eds.), Rethinking Negotiation Teaching: Innovations for Context and Culture (pp. 293–313). St. Paul, Minn.: DRI Press, 2009.

- Adaptive peacebuilding (PDF Download Available). Available from: www.researchgate.net [accessed Apr 23 2018].

- Dessel, A., Rogge, M. E., and Garlington, S. B. “Using Intergroup Dialogue to Promote Social Justice and Change.” Social Work, 2006, 51(4), 303–315.

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition. New York: Continuum, 2009.

- Galtung, J. “Cultural Violence.” Journal of Peace Research, 1990, 27(3), 291–305.

- Jones, T. S. “Conflict Resolution Education: The Field, the Findings, and the Future.” Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 2004, 22(1–2), 233–267.

- Lederach, J. P. Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures. Syracuse Studies on Peace Loode, Serge. Navigating the Unchartered Waters of Cross-Cultural Education. Conflict Resolution Quarterly. DOI: 10.1002/crq

- Pretty, J. N. A Trainer’s Guide for Participatory Learning and Action. IIED Participatory Methodology Series. London: Sustainable Agriculture Programme, International Institute for Environment and Development, 1995.

- Rothman, J. “Action Evaluation and Conflict Resolution Training: Theory, Method and Case Study.” International Negotiation, 1997, 2, 451–470.

- Shouldice, J., and Church, C. The Evaluation of Conflict Resolution Interventions: Part II: Emerging Practice and Theory. 2003. University of Ulster, United National University, Ulster. www.incore.ulst.ac.u (accessed April 29, 2011).

- Taylor, P. How to Design a Training Course: A Guide to Participatory Curriculum Development. London/New York: Continuum; VSO, 2003.

- Westoby, P. “Community-Based Training for Conflict Prevention in Vanuatu: Reflections of a Practitioner-Researcher.” Social Alternatives, 2010, 29(1), 15–19.

- Young, Douglas W. Prescriptive and Elicitive Approaches to Conflict Resolution: Examples from Papua New Guinea. Negotiation Journal. 14 (3), 211-220, 1998.

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

Innovators in Adult Education have recognised that adults learn differently than younger students and that, consequently, education techniques should be adapted to better meet their specific needs. Andragogy (adult learning) is based on Malcolm Knowles’ observations in the 1960s on the differences between adult and child learners. Principally, he argued that adults need to be involved in the learning process and empowered to bring their own insights to the learning experience. Adult learning is highly compatible with experiential education as identified by Kolb due to the value of learning from experience, problem-solving, and reflection. The engagement of learners and value in adapting to their needs also makes it highly compatible with Lederach’s elicitive model of learning.

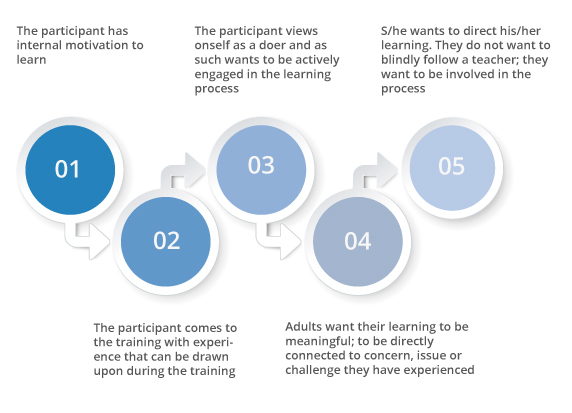

Knowles (2005) argued that:

- adults have an internal motivation to learn

- adults bring to the training a set of experiences that can be drawn upon during the training

- adults want to direct their own learning and consequently learn best when the trainer empowers them in this way

- adults want to be actively engaged in learning

- adults want their learning to be relevant to their lives and directly applicable to challenges they experience.

Figure: Pillars of adult learning

Based on these observations, Knowles devised four principles of adult learning in 1984. They include:

- adults need to be actively engaged in planning and evaluating learning

- adult education should be based on learning from experience

- learning should relate directly to work or challenges in their personal life

- adult learning should focus on problem-solving rather than absorbing content (Kearsley, 2010)

1) Applicability to Real Life

A trainer should ensure that learners understand the applicability of the learning to their lives and work at the time of the training. Adults want to know that the learning will benefit them now rather than in the distant future. Trainers can, through a needs assessment with participants before training and through conversations during the training, ensure that the subject matter will be relevant to the participants. Clearly showing the link between training material and real-life is key.

2) Participant Agency/Self-Direction/Co-creation

This can be done through needs assessments in advance of a training that give the participants a voice. Also, trainers can ensure participants help to direct their learning by giving them options of what they would like to focus on or devising exercises that give flexibility for participants to mould the learning to their particular needs. Finally, trainers can respond to participant’s questions and suggestions in the training and adapt the training if necessary.

3) Diversity

The trainer should be sensitive to the diverse needs of the learners. They should be prepared in a training to accommodate diverse learning styles, as well as cultural, gender and age differences. In addition, in relating the material to the real world, they should engage participants in reflection on how material would be applicable in different settings.

4) Focus on problem/experience/task over content

Participants should not be expected to passively absorb and memorise content; rather, they need activities that facilitate learning. Such activities allow participants to collaborate together on a problem, share a common experience, and reflect on the activity.

- It is compatible with other recommended approaches, such as the elicitive approach and experiential education.

- It adapts to needs of the participants.

- It ensures participants have a voice in the training.

- It focuses on real-world applicability.

- Ensuring material is covered within the time frame. Spending significant time hearing from participants can make the training significantly longer and risks not finishing in time.

- Mediating between participants’ training goals. Focusing on applicability of the training too narrowly on more vocal participants’ needs may alienate participants with different concerns.

- Trainers should ensure the training environment is a safe space for all participants to bring their issues and concerns to the table. This means setting ground rules and using introductions and ice breaking activities. Most importantly, one cannot let a few participants dominate the training.

- Methods should be geared towards participants working through problems or challenges together. They should be highly interactive. Participants would benefit from role plays and case studies that reflect real-life scenarios.

- Trainers should be prepared to give participants choices at times on what type of activity would benefit them the most and what subject matter to prioritise.

- Trainers should allow for feedback from participants before, during and after the training.

- Fras, M., & Schweitzer, S. (Eds.) (2016). Mainstreaming Peace Education Series. Designing Learning for Peace: Peace Education Competence Framework and Educational Guidelines.

- Gamson, Z.F. (1994). Collaborative learning comes of age. Change, 26(5), 44-49.

- INEE (ND). International Network for Education in Emergencies. Three Steps to Conflict Sensitive Education. www.iiep.unesco.org, retrieved on 26.03.2017.

- Kamp, M. (2011). Facilitation Skills and Methods of Adult Education: A Guide for Civic Education at Grassroots Level. Published under the project: “Action for Strengthening Good Governance and Accountability in Uganda”. Uganda Office, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung.

- Knowles, M. S., Holton III, E. F. & Swanson, R. A. (2011). Adult Learner. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis.

- Knowles, M. S., Holton III, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2005). The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development. Burlington, MA: Elsevie.

- Knowles, M. S. (1950) Informal Adult Education, New York: Association Press. Guide for educators based on the writer’s experience as a programme organizer in the YMCA.

- Knowles, M. S. (1962) A History of the Adult Education Movement in the USA, New York: Krieger. A revised edition was published in 1977.

- Knowles, M. (1975). Self-Directed Learning. Chicago: Follet.

- Knowles, M. (1984). The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species (3rd Ed.). Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing.

- Knowles, M. (1984). Andragogy in Action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Kearsley, G. (2010). Andragogy (M.Knowles). The theory Into practice database. Retrieved from tip.psychology.org

- Merriam, Sharan B. (2001). “Andragogy and Self-Directed Learning: Pillars of Adult Learning Theory.”

- New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. University of Georgia/Jossey-Bass.

- UMSL umsl.edu

- CAMP & Saferworld (2014). Training of trainer’s manual: Transforming conflict and building peace.

- CCIM. (ND). Facilitator Manual: Educator Role and Guidelines, Adult Learning Principles. Community Care Information Management.

- Community Support Services Common Assessment Project. (ND). Facilitator Manual: Educator Role and Guidelines Adult Learning Principles. www.ccim.on.ca, retrieved on 12.06.2017.

- Simply Psychology (2013). Kolb Learning Styles. www.simplypsychology.org, retrieved on 12.04.2017.

- Smith, M. K. (2002) ‘Malcolm Knowles, informal adult education, self-direction and andragogy’, the encyclopaedia of informal education, www.infed.org

- UMass Dartmouth (2017). Tips for Educators on Accommodating Different Learning Styles. www.umassd.edu, retrieved on 24.05.2017.

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

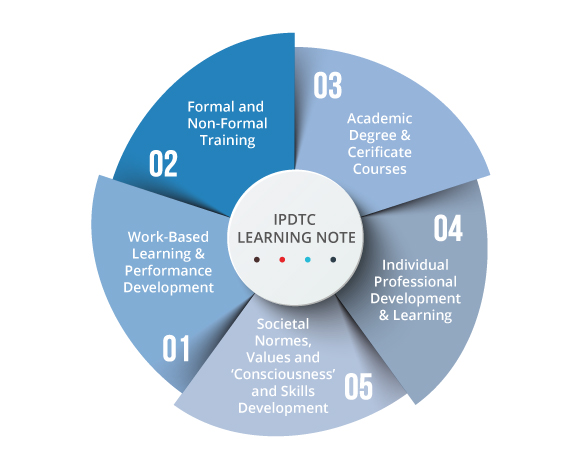

Work-based learning (WBL) refers to learning which takes place in the working environment – in an organisation, agency or mission – through participation in (i) work processes or (ii) accompanying learning processes integrated into the work space and practice. It is learning and capacity building embedded in the practice and processes of work. This provides a unique opportunity to improve competency of personnel for the specific roles and responsibilities they have in their position and missions/organisations.

WBL implies two characteristics: i. learning in a work context and ii. learning through work practice. In contrast to trainings which are often implemented in locations ‘separate’ from or outside of work, or degree programmes which take place before or in between work periods, WBL takes place on the job and, for many, in the field. While well developed in the business and, to some extent, in the NGO sector amongst larger organisations, work-based learning is an approach to capacity building and professional competency development that is substantially underdeveloped and underutilized in peacebuilding and prevention to date. Implementation of WBL approaches requires organisations, agencies or missions to consciously develop and put in place approaches, tools and practices for WBL. The concept of WBL can also be closely connected with and integrated into organisational learning approaches and is strongly linked to situated and experiential learning.

- 68% of employees prefer to learn at work

- 58% of employees prefer to learn at their own pace

- 49% of employees prefer to learn at the ‘point of need’

- 94% of employees would stay in an organisation longer if it invested in their career development

Source: LinkedIn Learning with Lynda.com Content, (2018) - 2018 Workplace Learning Report: The Rise and Responsibility of Talent Development in the New Labor Market, Found at learning.linkedin.com (accessed 17 April 2018)

Few organisations, agencies or missions today have in any way developed significant work-based learning approaches for peacebuilding and prevention. It is assumed that personnel / staff either (i) arrive with the competencies they require for their work or (ii) can develop the competencies they require through training programmes or (iii) pick them up along the way. There are three particular challenges to this line of thinking:

- Given the critical absence of skills-based training and competency development in most graduate programmes and lack of integration into academic courses of skills training on competency requirements for the field, most academic graduates lack experience or capabilities they need to perform in the field.

- Most training, with very few exceptions, is not sufficient in and of itself to develop required competencies

- The failure to develop appropriate work-based learning processes and practices in organisations means that the vast majority of potential learning in situ for practitioners and professionals on the ground is lost or underutilised

Universities and training institutions are seen as valuable places of learning, but the potential to learn from our actual work place and work in the field is often neglected

Increasingly the work place is being recognised not only as the space in which practitioners and personnel perform their work, but in which they (can and should) learn and develop improved competencies for their work.

Figure: Spaces for Learning & Professional Development – IPDTC Learning Note

In recent years, the European Union, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the International Labour Organisation (ILO) have all recognised the importance of WBL in vocational training. Characteristics of WBL include:

- WBL is situated learning that takes place in the context in which that learning will be applied

- WBL is learning that takes place in or through i. implementation of work processes and through ii. learning processes integrated into the work space and practice

- WBL allows exact customisation of learning processes to address competencies required for an individual’s specific role / position, organisation and context

- WBL provides a greater breadth of opportunity to pair learning to task performance and roles, enabling sequential evolution, experimentation, practice and application feeding back into further learning and development

- WBL can utilise both synchronous and asynchronous learning, allowing personnel to learn at the pace and approach that suits them best and improve ‘point of need’ learning

While WBL systems need to be customised to the roles, context and needs of the organisation/mission, and the role, position or competencies to which they are applied, the infrastructure, supporting materials and resources for WBL can be developed across the field or for specific sectors and then customised.

Learning competencies developed through WBL should be directly tied to the tasks being performed and competencies required for effective implementation of personnel’s roles. Some of the more common practices to support WBL include:

- apprenticeship, internship or mentorships/coaching

- job shadowing or embedded postings; field visits

- e-learning / ICT platforms for on-the-job / in-the-workplace learning support and capabilities development

- in work place simulations / exercising / role playing; collaborative design processes and red-team / green team development (where one ‘team’ brings forward an approach/method or project design and the other ‘team’ challenges and tests it to help identify gaps, assumptions, weak links and support overall design improvement)

- ex-ante evaluations, action evaluations, final or summative evaluations, and ex-post evaluations and learning reviews

- communities of practice; single agency, multi-agency or multi-sectoral retreats

- learning notes

- team learning and practice improvement sessions and reviews

- use of collaborative tools (for instance, WhatsApp) for sharing learning notes/messages; after action / after operations or events debriefs.

Given the breadth of WBL instruments and methods, effective implementation of WBL in a mission or organisation in the field requires a clear learning management system. Here, a learning management system is defined as the overall system of human resources development, training and strengthening of personnel and organisational competencies, and not as it is also sometimes used to refer to learning management systems for online learning only. In an organisation or sector-wide learning management system, competencies and learning objectives are clearly defined and matched to appropriate capacity building approaches, methods and practices within the organisation. Organisations may also consider ‘hybrid’ models combining in-position / work-based learning with online courses or training programmes. Importantly, WBL can also be applied through ‘sector’ wide systems within an area of operations or ‘organisation wide’ across areas of operation / countries.

- Learning is carried out directly in context and can (often) be applied immediately in work

- Learning can be more specifically tailored to exact roles, responsibilities and tasks of a position and the needs of an organisation

- Effectively developed WBL strongly strengthens worker satisfaction and staff retention

- Reduces time delay in addressing skills gaps in the field. Employees can engage in WBL’s as time and performance require rather than in response to the schedule of training programme delivery

- WBL systems which include collaborative practices and exercises in groups / teams can also improve collaborative efforts in task implementation and job performance

- Improved quality and higher productivity of teams / better impact

- Improving self-confidence and motivation

- Learn from practical realities in a way you never could in university / training

- Very new for the field. There have been few attempts to implement and few organisations at this point understand how to apply WBL in the field

- Time and interest / commitment of participants (staff) to do it. If not implemented well it can be perceived as another ‘imposed burden’ by staff

- High turnover in the field means that investment by an organisation in WBL may lead to improved staff capacity but that staff then moves on to another organisation. At a field level, however, improving WBL across organisations would also lead to significantly improved human resource capacity field-wide

- Management / Programme Manager / Head of Mission or Desk / Country Director support and encouragement for WBL is essential

Work-based learning is a distinct field of competency development and professional development from training – though missions may take a ‘blended’ approach combining and integrating WBL with both online and on-site trainings and courses. It represents a significant potential advance in the field, opening for missions and agencies to develop learning approaches integrated into work practices to improve reflection, lessons learned and professional development.

The traditional understanding of ‘professional development’ and capacity building held across much of the peacebuilding and prevention field focuses on education and learning that takes place in formal academic contexts and / or through training programmes. Much less and sometimes no attention is given to the role of work-based learning in peacebuilding and prevention missions and programming - though this has recently begun to change. The Civil Peace Service (CPS) model developed in Germany can also be considered in the context of WBL, with a significant component of the purpose of deployment being to improve practitioner learning in the field while supporting their contribution to peacebuilding and prevention.

WBL should be understood as closely linked to streamlining improved monitoring, evaluation and learning processes and the drive to foster learning organisations. This would require close engagement between human resources units / departments, monitoring and evaluation teams, programme personnel and training units / experts, to customise and create appropriate WBL systems for missions and agencies in the field. Today, there are a multitude of skills gaps affecting the quality of personnel performance in the field. These cannot be met effectively by conventional on-site and on-line trainings. In many ways, WBL represents the third pillar of an effective approach to capacity development and improving performance in the peacebuilding and prevention field.

- European Commission (2012), Vocational education and training for better skills, growth and jobs, Commission Staff Working Document, (SWD)2012 375 final, Strasbourg.

- European Commission (2010), A new impetus for European cooperation in vocational education and training to support the Europe 2020 strategy, COM(2010) 296 final, Brussels Europe 2020: A European strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth.

- European Training Foundation (2013), Work-based learning: benefits and obstacles - a literature review for policy makers and social partners in ETF partner countries”

- Milway, K, Saxton, A., (2011) The Challenge of Organizational Learning, Found at: ssir.org (accessed 17 April 2018)

- Kis, V. (2016), “Work, train, win: work-based learning design and management for productivity gains”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 135, OECD Publishing, Paris

- LinkedIn Learning with Lynda.com Content (2018), Workplace Learning Report: The Rise and Responsibility of Talent Development in the New Labor Market, Found at learning.linkedin.com (accessed 17 April 2018)

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

Experiential Learning (EL) approaches to training are those in which participants learn by doing (Felicia, 2011). Experiential learning immerses participants in an experience. This can include both on-site real time immersion and experiential learning in work-based or training contexts (through role-plays, simulations, applied practice sessions and exercises), as well as on-line simulations, gaming and immersive experiences. In CPPB training this can include everything from 4-wheel drive to applying mediation practices or simulating addressing critical incidents (such as the outbreak of violence), trauma counselling and more. Participants engage in the experience and then reflect on the experience to facilitate development and transformation of knowledge, skills and attitudes (Lewis et al., 1994). EL is learning through the combination of i. doing and experiencing and ii. reflecting on the experience. Participants are the active protagonists both in the experience and in learning through reflective practice, rather than the passive recipients of knowledge transferred through rote or didactic learning (Beard, 2010).

In Experiential Learning (EL) participants are directly involved in the experience – either as participants or witnesses/observers. The use of witness / observer is not as widely practiced in Experiential Learning but has proven highly valuable in CPPB training and adult learning. While some participants are immersed in the experience, other participants take the role of ‘observers’ to watch what is being done and observe how those in the practice are doing. They may sometimes be given suggested guidelines or specific issues to focus on. This can be a very valuable technique which enables observers to learn from watching the experience, and enables observers and participants to both benefit after, during the reflection and review where observers share their perceptions on what happened and provide feedback and suggestions. This reflective practice can often help participants become aware of issues they may not have noticed when in the midst of an immersive experience.

In Experiential Learning, participants are the protagonists of the learning experience – learning, developing, testing and challenging their knowledge, skills and attitudes through the combination of doing – exercising and being immersed in an experience – and reflecting on the experience. This builds upon understanding of how competency is developed, where participants have the greatest retention when learning involves actively doing and not only passively receiving. EL recognises the importance of being immersed in practical situations and exercises. This can range – in CPPB training – from exercising skills for 4-wheel all-terrain drive to de-escalating crisis situations with conflict parties, engaging with community stakeholders, simulating responses to traumatic incidents or trauma care and support, exercising mediation practices and more.

A distinction should be made between EL which is 1. field-based and 2. EL in a training room setting. Field-based EL can include (but is not limited to): work-based learning, participatory action evaluation on practical experiences, simulations an exercises. Training-based EL can include (but is again not limited to): role-plays, simulations, serious gaming, group exercises, forum theatre and more (Lewis et al., 1994).

The role of emotions and feelings, of real time ‘in the moment’ reactions, the dynamics of interaction, together with the experience of relationships, of engaging and interacting and working to apply knowledge, attitudes and skills to actual situations and practice are what Experiential Learning is about (Moon, 2004). Participants are involved and involve themselves in the experience, and then use reflective practice and analysis to gain a better understanding of the learning to be drawn from the experience. It is hands-on, applied learning and learning by doing to improve actual skills and operational performance and capabilities for the field.

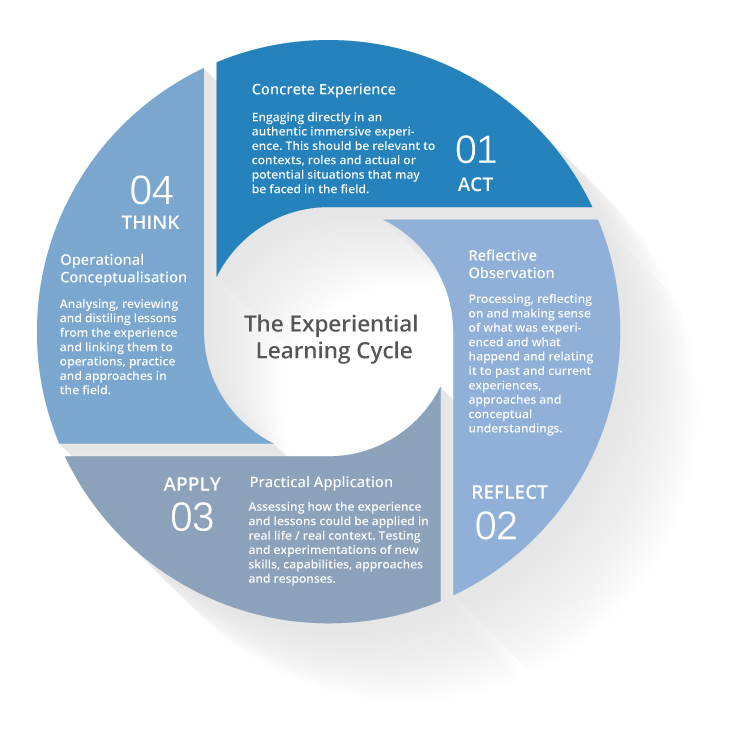

The Experiential Learning Cycle developed by Kolb and Fry (1975) identifies 4 components:

- The concrete experience

- Reflective Observation

- Conceptualisation

- Application

These are reflected in the model below adapted from several presentations of Kolb and Fry’s approach and tailored somewhat to the CPPB training context:

Figure: The Experiential Learning Cycle, adapted from Kolb and Fry (1975)

As suggested by Wurdinger (2005) and Schwartz (2012), experiential learning involves a mixture of both primary and secondary experiences. Primary experience refers to the experiential activities themselves. Secondary experience results from the primary experience through the reflection carried out on the primary experience. To make the reflection and learning element as effective as possible, Moon (2004) suggests it should include 3 elements:

- The reflective learning and observation phase

- Learning resulting from actions inherent to experiential learning – the actual ‘learning from doing'

- Learning from feedback

Applying reflective practice develops participants own capacity to learn from experiences, strengthening their capacity to improve or develop new knowledge, skills and attitudes. Trainers applying EL need to think through both i. how they will prepare and implement the experience(s); and ii. how to best facilitate reflection and learning on the experience(s). It should be noted that EL lends itself to what is known as the scaffolding approach to training, whereby successive iterations of action and reflection develop cumulative transformative impact on participants’ attitudes, skills and knowledge (much like the building of a scaffolding). Learning as an iterative process continuously builds on further practice and reflection (Kompf & Bond, 2001, p55).

The following is a list of characteristics of Experiential Learning drawn from Chapman, McPhee and Proudman (1995) and adapted (slightly) for application to CPPB:

- Balance content and process: There must be a balance between the experiential activities and the underlying content and competencies required.

- Ensure a safe learning experience: The trainer must create a safe space for participants to work through the process of self-discovery and reflective learning.

- Relevance & purpose: In experiential learning, the participant is the self-teacher. The experience and reflective processes must be relevant and have meaning and value for the participant and her/his context and performance needs.

- Make connections: EL should help participants make the connection between the learning they are doing and its real-world application. Activities should build in the actual nuances, complexities, issues and challenges they will face in practice, helping participants 'see relationships in complex systems and find a way to work within them'.

- Embed reflection: Reflection is central to EL. Participants should be supported, assisted and empowered to be able to engage in and apply effective reflective practices together and on their own to be able to bring the experience to life and gain insights into themselves, peace and conflict dynamics, the human experience and CPPB in the field which can assist their interactions and performances in the real world.

- Create investment: Participants should be fully immersed in the experience, not merely doing what they feel is required of them. The “process needs to engage the learner to a point where what is being learned and experienced strikes a critical, central chord within the learner.”

- Create a safe space to identify, challenge and re-examine attitudes, values and approaches: By working within a space that has been made safe for self- exploration and learning participants can begin to analyse and even alter their own attitudes, values and approaches / practices – both those they have been consciously aware of and those they haven’t. This is one of the most powerful benefits of experiential learning.

- The presence of meaningful relationships: One part of getting participants to see their learning in the context of the realities of the world and actual conflict dynamics and experiences is to start by bringing forward and enabling participants to experience the relationships between i. practitioner to self, ii. practitioner to communities in which they are embedded, and iii. practitioner to the conflict or process they are engaging in.

- Learning outside one’s perceived comfort zones: Experiential learning can be one of the most effective ways of enabling participants to gain experience and insight operating outside their known or unknown ‘comfort zone’ in the relative safety and care of a facilitated process. This can assist participants to become aware of and understand the need to engage with latent or unconscious attitudes, assumptions and practices which may cause harm or fail to do good, and to improve accountability and ownership of their actions (or inactions) and consequences.

- Allows participants to ‘experience’ situations and issues they will face or have faced in the field, and to engage with, test and challenge attitudes, knowledge, skills and practices which may positively or negatively affect peacebuilding impact on the ground

- Creates a safe space in which participants can work through improving performance capabilities on tasks and issues they may face in the field

- Can be used for ‘debriefing’ and ‘re-enacting’ difficult, challenging or sometimes traumatic experiences and assist participants to work through options and improve future practice. By bringing forward potentially hidden impacts and continuing effects of traumatic experiences in a safe context EL can help to reduce risk to participants and others in the field

- Can make issues more ‘tangible’ and real to participants

- Can improve quality of response/practice in the field

- Can help apply and connect ‘theoretical concepts’ to practice

- Improves participants capacities to reflect on and adapt/evolve attitudes, understanding and approaches more effectively than passive learning techniques

- Can help reduce the likelihood of risk and impact of trauma in the field

- If not implemented well / skilfully or without proper debrief it may only reinforce bad practices or patterned behaviour without enabling evolution and improvement

- Participants may ‘reject’ experiences which challenge them or would require them to adapt/evolve/improve their practice, attitudes and knowledge if experiences are not handled skilfully

- Experiential practices can also trigger both immediate or delayed trauma, anxiety and stress related to participants experiences in the field or personal lives

- If preparation for experiential processes is not done well and given the time it needs, the learning value of the experience may be reduced

- If debrief and review are not done well or given the time they need, the learning value of the experience may be reduced

Experiential Learning techniques are increasingly seen not only as being at the forefront of the CPPB field but as being essential and fundamental to proper CPPB training. For any competencies which require performance capacity in the field, integration of EL techniques in training is essential. Increasingly, EL is being implemented across all 3 core spaces of CPPB training: on-site, on-line and in work-based learning. Examples of EL in CPPB can include:

- Multi-hour / multi-day simulations of key situations practitioners may face in the field – e.g. enacting a response to a crisis or outbreak of violence

- Simulations or role-plays of mediation or peace processes exercising different moments in the process

- Applied practice in the field implementing community-based peace and conflict analysis with a coach or with post-action debrief and review to support improving practice and performance

- Utilisation of action evaluation or post-action evaluation in the work context to improve next steps / future programming

- Use of serious gaming or full immersion simulations online

CPPB trainers / training institutions may themselves need to be trained in how to do EL well. Ensuring a do no harm approach and being aware of how EL can trigger traumatic experiences and memories is essential. Trainers should also be aware of issues of personal and physical space, gender, safety concerns, and how people’s personal and societal cultures may affect their experience and engagement in EL, and EL debriefing and review. For more elaborate EL or EL which may trigger traumatic relapses/experiences, this needs to be engaged with carefully and trainers/training teams may wish to have a trained counsellor on hand to support after-action debrief and direct counselling for participants.

Avoiding superficial approaches is also important. Single ‘exercises’ or ad hoc and quickly put together simulations or role plays can cause as much damage as good. Doing one single ‘exercise’ in a training may make the training more interesting for participants and may be better than doing none at all, but is not the same as ensuring effective competency development which may require many hours of simulations, role plays or other EL practices.

There is tremendous potential for wider application of EL in CPPB training. This could include identifying core competencies required for CPPB and then developing packages of EL approaches which could support these that could be used by trainers and training institutions.

- Anderson, H. M. Dale’s Cone of Experience. University of Kentucky. Retrieved from www.queensu.ca

- Beard, C. (2010). The Experiential Learning Toolkit: Blending Practice with Concepts. London: Kogan Press.

- Chapman, S., McPhee, P., & Proudman, B. (1995). What is Experiential Education? The Theory of Experiential Education, 235-248.

- Felicia, P. (2011). Handbook of Research on Improving Learning and Motivation through Educational Games. Hershey, Pennsylvania: IGI Global.

- Firestone, M. What is Experiential Learning? - Definition, Theories & Examples. Retrieved from study.com

- Jarvis, P. (1995) Adult and Continuing Education: Theory and practice 2. London: Routledge.

- Kolb. D. A. & Fry, R. (1975). Toward an applied theory of experiential learning. Theories of Group Process, 33-58.

- Kompf, M. & Bond, R. (2001). Critical reflection in adult education. The craft of teaching adults, 55.

- Lewis, L. H. & Williams, C. J. (1994). Experiential learning: Past and present. New directions for adult and continuing education, 62, 5-16.

- Moon, J. (2004). A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Schwartz, M. (2012). Best Practices in Experiential Learning. Ryerson University Learning and Teaching Office.

- Wurdinger, S.D. (2005). Using Experiential Learning in the Classroom. Lanham: Scarecrow Education.

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

A sequenced approach to training, also often referred to as a phased, progressive or layered approach, refers to a systems approach to training in which different competencies and/or different levels of competencies are trained in different programmes. Participants progress in sequence through different trainings depending upon the competencies / performance levels they require for their positions / roles and/or their levels of expertise / performance and competence for the task. A classic progression in sequence trainings is from lower order to higher order or introductory / foundation courses through core skills training to advanced, specialisation and expert courses. While sequenced training is widely used in the military with allocation of training to different roles and ranks, it has not yet been systematically or widely applied in CPPB training and professional development – largely due to the absence of agreed competencies frameworks and lack of common / shared systems approaches to training (SAT) in the CPPB field.

Sequential approaches refer to the sequenced or phased delivery of trainings. While this is most often taken to refer to the delivery of different training programmes sequenced by level, competency or complexity/difficulty, it can also refer to the sequencing of content, modules and methods within a single course or training module. The essential concept in a sequential approach to training is that participants require competency at one level – on an issue, skill, technique – before moving on to further trainings at higher levels. According to Sequencing and Structuring Learning Activities in Instructional design, trainings can be sequenced according to:

- Job performance order or rank: with different competencies and levels or types of training sequenced according to competencies required for different roles and ranks.

- From Simple to Complex: with learning objectives and competencies sequenced in terms of increasing complexity.

- Known to Unknown: familiar topics considered before unfamiliar ones.

- Dependent Relationship: where mastery of one competency or learning objective is required prior to mastery of another.

- Supportive Relationship: where different competencies and learning objectives are closely related and transfer of learning takes place between them. When this is the case, different trainings should be placed as closely together as possible to reduce decay / loss of learning.

Two additional critical considerations in sequential training relate to:

- Training for performance in stressful situations: testing has shown that sequential approaches to improving practitioner competency and performance under high stress conditions or high stress tasks can improve learning results, phasing between training on a task in a stress-free (‘low fidelity’) training to trainees being exposed to stressors of a kind and intensity that more accurately reflect actual conditions they may face in the field (‘high fidelity’ training). For CPPB this consideration is a crucial one as many trainings – particularly those reliant principally upon prescriptive content delivery – fail to develop competencies sufficiently for performance requirements in the field or fail to prepare participants for actual conditions in which they will engage in the field.

- Point-of-Delivery Training: where basic, foundation or even advanced and expert-level trainings delivered outside the field or earlier in time are then complemented by on site field-based trainings, coaching or experiential practice immediately before ‘point of delivery’ on key tasks and roles. An example of this can be participants who have taken previous training on either peace and conflict analysis or mediation and peace processes receiving further, more advanced, hands-on and practical / applied training in the field or in the moment immediately before application – to refresh knowledge, improve skills, and improve capacity to perform to task

Most training today in the CPPB field is not sequential / phased, because trainings are developed as ‘stand-alone’ modules or individual modules within trainings are delivered with little connection to higher order skills and performance requirements. This is largely due to the absence of a comprehensive competency framework or systems approach to CPPB training shared across training institutions. While many training providers do provide different ‘ranks’ or ‘levels’ of training – ranging from basic / introductory to advanced and expert, specialisation or senior-level trainings, differentiation is usually based upon ‘years of experience' in the field or, at times, rank/role/position, but may not relate to participants having received earlier / lower order prior trainings.

There is extensive evidence from military, sports, and medical training that sequential or phased training is a leap forward in training and learning sciences to increase practitioner retention and support development of higher order competencies and skills. Sequential training can also play a key role in increasing retention, solidifying past learning, and improving participant capabilities to perform under stressful or challenging contexts – all specifically relevant to the conditions faced by many CPPB practitioners.

Sequential or phased training requires a development or maturity of the CPPB training sector as a whole that has not yet been attained in the field. With the absence of a comprehensive competency framework for CPPB training or common (baseline) standards for levels, approaches and methods of training across most competencies, this represents a quality standard that CPPB training in Europe has not yet attained. The potential is there, however, as the CPPB training field takes steps to improve and with obvious examples available both from related fields (e.g. military training) and earlier forerunners in the field, such as Peace Workers UK which developed a sequenced approach to CPPB training in the early 2000s including different levels of training and different competencies or levels of proficiency in those competencies required for each level.

Implementing sequential or phased approaches to training can either be done piecemeal or as a field evolution. Piecemeal implementation would refer to introduction of sequenced approaches either by:

- single / individual training institutions or national training systems or

- on single competency fields / areas of practice – such as creating different ‘levels’ of training according to complexity and mastery of competencies on issues such as peace and conflict analysis, mediation and peace processes, or preventing and managing crisis and critical incidents

A field evolution approach would involve several training institutions or CPPB training providers across Europe or more broadly agreeing to a common competency framework and systems approach to training in which different training levels / units are developed according to different learning objective requirements, competencies and complexity/difficulty levels.

Training institutions, deployment agencies, trainers and policy makers in Europe – as well as more broadly internationally – should consider the proper development of sequential training in the CPPB field as a natural and necessary next step to improve the quality of training, itself needed to improve the quality of competencies and capabilities in the field.

- CDC. CDC Unified Process Practices Guide: Training Planning. Retrieved from www2.cdc.gov

- Clark, D.R. (1995). Sequencing and Structuring Learning Activities in Instructional Design. Retrieved from www.nwlink.com

- DeWeese, B. H., Hornsby, G., Stone, M., Stone, M. H. The training process: Planning for strength–power training in track and field. Part 1: Theoretical aspects. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 4(4), 308-317. doi.org

- Keinan, G., Friedland, N., Sarig-Naor, D. V. (1990). Training for Task Performance Under Stress: The Effectiveness of Phased Training Methods. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 20(18), 1514-1529. doi.org

- Ministry of Defense of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Policy for Individual and Collective Military Training. Retrieved from www.mod.gov.ba

- Ritter F. E., Nerb, J., Lehtinen, E., O’Shea, T. (2007). In order to learn: how the sequence of topics influences learning. Oxford series on cognitive models and architectures. dx.doi.org

- Stone, P. (1998). Layered Learning in Multi-Agent Systems. (Doctoral dissertation). School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh.

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

While it is specifically a method of performance and capabilities improvement, ‘coaching’ is used here to describe also an entire approach to improving performance competencies which also includes related methods such as counselling and mentoring. As an approach, coaching represents ‘one-on-one’ processes providing customised, tailored support to improve performance and capabilities of the practitioner. It is an interactive, ‘future-focused’ process which supports the practitioners' potential and enables them to improve capabilities and maximise performance. In peacebuilding and prevention, coaching is increasingly used to enhance capabilities and performance in the field, including: for senior mission leadership; to support mediators in mediation processes; to assist conflict parties in negotiations; and to assist leadership in high-level organisational and mission implementation challenges. There is significant potential for the further expansion and use of coaching in CPPB including to improve results of training and as an instrument to substantially enhance practitioner and mission performance and capabilities in the field.

Coaching as an approach to improving capabilities and performance is widely practised in sports, business, psychotherapy, counselling, life improvement and organisational development. Beginning with the early 2000s it has gradually beenintroduced into CPPB from two directions: i. facilitation of organisational change and executive performance and ii. support to senior leadership and practitioners in the field. In organisational change and executive performance, large missions and organisations have at times used coaching to support executives / senior staff in addressing issues of mission performance and organisational or institutional development. In support to senior leadership and practitioners, coaching is increasingly used to assist senior leadership of conflict parties as well as mediation and negotiating teams and mediators to assist them in working through conflict situations and handling mediation processes. Coaching as an approach to performance improvement and capacity building has particular relevance for the CPPB field. As personnel often operate in highly challenging, fluid contexts working to achieve difficult goals under sometimes complex and stressful contexts, coaching can provide a tailored, targeted approach to assisting practitioners, senior leadership and parties in conflict to more effectively address the issues and challenges they face. Drawing from experiences in sports coaching, business, counselling and life improvement, coaching may also help to address many of the gaps that performance training is not able to do.

Coaching is significantly different than training. It is usually a one-on-one process though it can also be provided to small groups where practitioners/participants are facing similar roles, issues, contexts, challengers or objectives. It is traditionally delivered in situ in the work context or processes in which the client / practitioner is engaged. The aim of coaching is not necessarily to ‘transfer’ or elicit pre-established skills and competencies, but to enhance a practitioner’s capability to address a specific task or improve performance on a specific goal or process. Practitioners are seen as capable, creative individuals with experience. The task of the coach is to assist them to bring their best to the situation and master skills and approaches needed for the moment. Coaching involves providing a listening space, assisting with feedback, helping practitioners ‘work through’ their logic and approach to specific issues, assisting reflective practice, and facilitating self-directed learning. Coaching is normally delivered ‘face-to-face’ through in person direct interactions. In recent years, however, an entire field of online coaching through skype and other interactive platforms which allow for direct video conferencing and ‘face-to-face’ communications online has developed.

In Everything you ever wanted to know about coaching and mentoring the following characteristics are identified:

What coaching does

- Facilitates the exploration of needs, motivations, desires, skills and thought processes to assist the individual in making real, lasting change.

- Uses questioning techniques to facilitate client’s own thought processes in order to identify solutions and actions rather than takes a wholly directive approach.

- Supports the client in setting appropriate goals and methods of assessing progress in relation to these goals.

- Observes, listens and asks questions to understand the client’s situation.

- Creatively applies tools and techniques which may include one-to-one training, facilitating, counselling & networking.

- Encourages a commitment to action and the development of lasting personal growth & change.

- Maintains unconditional positive regard for the client, which means that the coach is at all times supportive and non-judgemental of the client, their views, lifestyle and aspirations.

- Ensures that clients develop personal competencies and do not develop unhealthy dependencies on the coaching or mentoring relationship.

- Evaluates the outcomes of the process, using objective measures wherever possible to ensure the relationship is successful and the client is achieving their personal goals.

- Encourages clients to continually improve competencies and to develop new developmental alliances where necessary to achieve their goals.

- Works within their area of personal competence.

- Possesses qualifications and experience in the areas that skills-transfer coaching is offered.

- Manages the relationship to ensure the client receives the appropriate level of service and that programmes are neither too short, nor too long.

In Executive Coaching: Inspiring Performance at Work by Carter coaching is identified as :

- Short term, time-limited

- Goal specific

- Action and performance oriented

- Personally tailored approach to learning

Carter goes on to identify 5 ‘moments’ when an organisation or personnel might benefit from coaching:

- Supporting induction into a more senior role – to ease the process of transition

- Supporting high performers / staff to achieve their performance potential

- Supporting new phases in programmes or major structural or institutional change – accelerating the time that would otherwise be taken to achieve buy-in and effective implementation of change

- Helping to address challenges, tasks, processes or contexts

- Supporting personal effectiveness of individuals as part of a more comprehensive development programme or process – such as 360-degree feedback programmes and executive leadership training

Different ‘types’ of coaching have also been identified, including:

- Organisational Coaching: intended to help individuals / staff learn key roles and processes in a mission or organisation. This is often applied in the context of induction to improve the speed of taking on a new role in an organisation effectively

- Executive Coaching: providing support to senior mission or organisational leadership to address the challenges they face in executive decision making and handling often complex and sometimes high-risk or sensitive issues

- Performance Coaching: intended to help practitioners improve performance either on specific issues, processes or tasks or overall

- Skills Coaching: focusing on core skills a practitioner needs in their role

In Executive Coaching: Inspiring Performance at Work, a table developed by the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) differentiates executive coaching – as a method - from other processes also covered here in coaching as an approach:

| Process | Originating Tradition | Primary Concern | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Coaching | Sports |

|

Rapid acquisition of knowledge, skills and behaviours |

| Psychotherapy | Social |

|

Dealing with long-standing emotional issues, thoughts and ways of behaving |

| Counselling | Social |

|

Coming to terms with event(s) |

| Mentoring | Apprenticeship |

|

Enhancing networking and career progression |

| Organisation Development | Change |

|

Rapid implementation and adaptation to change |

Coaching provides highly customised, tailored support to improving performance. It is able to engage with the exact conditions, context and needs both of the practitioner/client and of the organisation / process. It enables a nuanced engagement far more thorough and comprehensive than is generally possible in training or other standardised processes. As will be seen below, coaching can also be used in a blended approach or as an element of a comprehensive capacity building programme, including in pre-, during- and post-training. Evidence from the sports sciences, business and psychotherapy fields show that coaching, when done effectively, provides a high return on investment. In CPPB, it may address a critical ‘missing link’ in support needed for practitioners in the field, particularly for high-level mission leadership and parties involved in mediation and peace processes or leadership in prevention and peacebuilding.

As generally practiced, coaching is limited to ‘one individual at a time’ – though a coach may work with several individuals in different processes simultaneously. It requires having someone ‘on staff’ for the role. This may be an investment well worth it for middle to larger size organisations and missions, but is not always possible for smaller missions. Because of the direct relationship involved in coaching, strict adherence to ethics, non-discrimination, and non-harassment policies are essential. There can also at times be the challenge of the practitioner and coach not ‘connecting’ or syncing well together. If the model and approach to coaching used by the coach doesn’t fit the needs of the individual, the organisation or process results may also not be those desired. Importantly: organisations or missions which implement coaching – recognising the substantial benefits it can achieve – must also be aware of possible perceptions of ‘unfairness’ if coaching is available to some staff / roles / positions and not to others.

Coaching as an approach to capacity building and performance improvement has only gained limited practice in the CPPB field to date. Some sectors – in particular police – using ‘mentoring’ (included here in the overall ‘approach’ of coaching) to support new personnel when they join the force or enter new positions. Some governments have begun introducing coaching for senior level institutional roles / positions – including coaching on gender-sensitivity to see how it can be applied in practice in policy and operations. Coaching is also increasingly recognised as an important tool to support local organisations and partners in capacity building, as training in and of itself is insufficient. Some organisations, such as ForumZFD and the International Peace and Development Training Center (IPDTC) of PATRIR also implement coaching as an integrated component in training programmes. Here coaching can be used pre-training to help prepare participants to take part in the programmes and gain greatest benefit from them, during programmes to assist learning and working through processes, practices and content in the trainings, and post-training to help retention and support application of what was learned in the training to specific roles and task performance.

- Campbell, J. Coaching and ‘Coaching Approach’: What’s the Difference? Growth Coaching International. Retrieved from www.growthcoaching.com.au

- Carter, A. (2001). Executive Coaching: Inspiring Performance at Work. Retrieved from www.employment-studies.co.uk

- Deane, F.P., Andresen, R., Crowe, T.P., Oades, L.G., Ciarrochi, J., Williams, V. (2014). A comparison of two coaching approaches to enhance implementation of a recovery-oriented service model. Adm Policy Ment Health, 41 (5), 660-667. doi.org

- Hawkes, M. E. (2016). Enhancing performance: An exploratory study of performance coaching in practice in a UK conservatoire. A&HHE Special Issue (August). Retrieved from www.artsandhumanities.org

- Noble, C. (2005). A Coach Approach For Conflict Management Training. Mediate.com. Retrieved from www.mediate.com

- Smith, R. E. (2010). A Positive Approach to Coaching Effectiveness and Performance Enhancement. Applied Sport Psychology: Personal Growth to Peak Performance, 6, 42–58.

- Taie, E. S. (2011). Coaching as an Approach to Enhance Performance. Journal for Quality and Participation, 34(1).

- The Coaching and Mentoring Network. Everything you ever wanted to know about coaching and mentoring. Retrieved from new.coachingnetwork.org.uk

- Yirci, R., Karakose, T., Kocabas, I. (2016). Coaching as a Performance Improvement Tool at School. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(13), 24-29.

Further reading

Find more information about the topic in our Peace Training Handbook .

Introduction

An Ecological or ‘Own Knowledge Systems’ (OKS) approach to CPPB training focuses explicitly on integrating and including knowledge systems and references from communities and countries affected by conflict into CPPB curricula. In an Ecological or OKS approach, methods and practices which are inspired and developed from within communities affected by conflict are recognized and valued as much as approaches and practices more conventionally addressed in CPPB trainings. Ecological approaches draw upon the latest advances and developments in the field while being – at the same time – embedded in practices from within communities and cultures in which CPPB programming is being done. While a formal defining of this approach has not been formulated in the field until now, Peacetraining.eu advances the ecological or OKS peace training approach as one characterized by awareness and engagement with the knowledge, traditions, culture, values and practices of communities globally, and honouring and respecting those communities affected by conflict in the knowledge, methods, approaches and content of CPPB training.

Going further into the framing of the ecological peace training or OKS as an approach and concept, without excluding key positive features of either traditional or modern knowledge management and peacebuilding approaches, key features and ideas of this approach are:

Figure: Ecological training: key characteristics

When considering the approach modelled above, and also the continuous question of how CPPB training could in practice become more locally considerate, locally relevant, locally effective, locally respectful, locally empowering and at the same time globally relevant and sustainable. In practice several possibilities arise:

Content: infusing the curricula with content which is authored and produced locally or relevant to the principles of ecological peace training.

J.P. Lederach’s approach to conflict represents an example of how his theoretical model is infused by elements pertaining to the traditional/indigenous knowledge management realm. Lederach’s elicitive and faith-based conflict transformation and peacebuilding model is a sounding board of these principles. Many CPPB training courses increasingly have this author amongst their bibliographies, thus making this an example of how at the content level this approach is being practiced.

Transitional justice experiences, especially those implemented in African countries, represent another example of how indigenous practices appear in CPPB curricula. Several case studies, such as the truth and reconciliation commissions of South Africa, are some of the good practice examples taught in CPPB training programmes. Considering the importance placed in traditional peacebuilding approaches on restorative practices, a clear recommendation for the training field is to: “Direct capacity-building programmes in the area of transitional justice in general, and the potential role of traditional mechanisms and practices in particular, towards the establishment of South–South networking initiatives and reciprocal exchanges of expertise” (Huyse and Salter, 2008, p.197). Methods: using methods which are home-grown Indigenous-inspired methodologies are mostly used within the civil society training realm, and even there they are quite limited. Probably the element that is practiced across-the-board with different training actors audiences is the use of circle processes and reflective practice, which, even if starting as an innovative setting in formal training spaces has gained ground and it is currently widely used as a symbolic reflection of the community of learning, of the participation of learners and also the wholeness of the process itself.

A specific method which is also used relatively widely is storytelling. A core practice of indigenous communities, storytelling involves the sharing of one’s own or other people’s stories within a social, artistic or, increasingly so, educational space. Encouraged more and more also in training programmes, storytelling brings the andragogical benefit of relating to one’s own reality, bringing this reality into the learning community and also has powerful effects in terms of healing, communication and connecting to others. Storytelling also involves complex relationships between the narrator and the audience, relationships which often, through the very familiar and universally accepted format of a story, transcend power dynamics. While examples of personal stories bringing about significant change abound in training they are also brought through the use of film and theatre. Indeed these examples are most often found in the arenas of civil society and academic training and capacity building.